I’ve been hunting for a thank-you card for Margaret Atwood for weeks now. This is such a big deal to me—getting the right card—that I’m about to lose my sh*t.

I’ll explain why about the card, but first, you understand why this is so huge, right?

I’m talking about THE Margaret Atwood. The Literary Goddess, Margaret Atwood. The one Poetry Foundation calls “one of Canada’s finest living writers.”

Whatever, Poetry Foundation. Atwood is one of the finest writers from ANYWHERE. EVER.

Atwood can write anything. She’s a poet, novelist, story writer, essayist, and literary critic. She’s authored more than forty books, won a zillion awards, and continues to tackle new, interesting projects, including a graphic novel and her most recent novel, Hag-Seed, a re-telling of Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

All this Atwood amazingness is, in part, why I can’t find anything good enough or right enough in my local card shop. Because how could a piece of cardstock—even high-end, embossed, self-consciously arty cardstock—ever adequately express my immense respect and admiration for this lovely human, let alone my gratitude?

I’ve never been the type to get celebrity crushes, being raised too much of a pragmatist. I wasn’t one of those ‘80’s kids who read Tiger Beat or obsessed about Kirk Cameron or put up posters of Patrick Swayze, and perhaps because I worked in politics for many years, hobnobbing with important people doesn’t faze me. But writers are kind of an exception.

Because books change lives, people!!!

Atwood’s The Edible Woman was one of the most impactful novels I read during my college years, and before that, her poetry. I was born on a cold day in Alaska in 1973, and the next year Atwood published her poetry collection, You Are Happy. I don’t own the collection, but twenty-three poems from You Are Happy are included in her Selected Poems 1965-1975, which I DO own. I don’t remember buying Selected—was it a gift?—I’ve just always had it. First published in 1976 it’s been around nearly as long as I have.

When I started writing poetry (awful, embarrassing stanzas about God and boys and being isolated), I read Atwood and wondered how she did it. How did she access that glorious and mysterious word magic? How do the five short stanzas in her title poem “You Are Happy” capture such a vastness?

Me on the frozen beach in Kenai, Alaska.

That poem speaks directly to me, a rural Alaskan girl, in part because I know how it is to be surrounded by a frozen landscape like the one described in the poem. My mind has many times arrived at the clarity of the body facing off against physical elements. I have experienced piercing cold and seen first-hand nature’s beauty and brutality. I know vulnerability and smallness, have walked in meditative solitude through the natural world and have trembled from the fearful seclusion one often finds there.

In short, I connected with Atwood’s poetry. Her themes of survival, images of the body, and the implicit questions about what it means to be female reached inside me and shook me. Slowly, on the cusp of twenty years old, I began to wake from a dark, oblivious sleep. Atwood’s words, alongside those of Adrienne Rich and Sharon Olds and Marge Piercy and so many other great women poets, birthed me into the world of literature. Not surprisingly, I am also a writer. My first novel, set to be released in fall 2017, would not be what it is without Margaret Atwood.

In the card shop, I assess options. How do you pick out a card for a literary mother, a woman who doesn’t know you—shouldn’t know you—who you will likely never meet? I remind myself that this is a business transaction. I will not address the card Dearest Margaret, nor will I overuse the word “love.”

It is often hard to separate the work from the writer—to know one is not to know the other. I don’t actually know Margaret Atwood despite knowing her work, and the fact is, all my gooey feelings for her are mine to hold. Sobbing in a  card shop is unseemly, yes, but more important, my charge is to laud and thank this esteemed writer not gush about my feelz. When I pen my message to The Margaret Atwood, it’s critical that I stay professional and avoid making an a$$ of myself.

card shop is unseemly, yes, but more important, my charge is to laud and thank this esteemed writer not gush about my feelz. When I pen my message to The Margaret Atwood, it’s critical that I stay professional and avoid making an a$$ of myself.

I am currently working with Portland State University’s Ooligan Press on the final edits to my novel, but during the deep revision part of the process, facing the stark landscape of the page often seemed impossible. What was my novel trying to say? I became small and vulnerable and isolated. Who was I? What did I have to say? I trembled in fear. I meditated in solitude.

I returned to Selected, my origin poems, seeking Atwood’s advice, inspiration and direction, and eventually found what I needed in Atwood’s “Circe/Mud poems.” I considered and reconsidered what it means to grow up rural, to be a woman in this country, and to be a female sexual being. I finished revising, and changed the ending of the novel.

Fifteen of Atwood’s words—four lines—kept repeating in my head. I thought, How perfect these lines would be as the novel’s epigraph. But how could I make that happen? I’m nobody. This is my first book, and the novel is being published by a small university press. Who do I ask? How much would it cost?

Months went by as I worked up the courage to send an email asking for permission. I researched Atwood’s literary agents (there are many). I emailed my publisher to get the information I needed to fill out the rights permission form that, as it turned out, was for the wrong agency, so my first email landed in the wrong literary lap. That woman, however, was kind and directed me to the correct agent and after a quick redraft, I sent off my request.

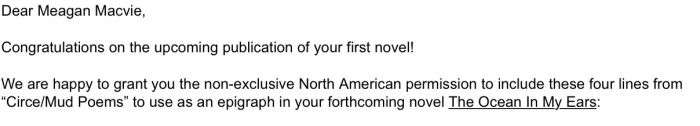

I tried to put the request out of my mind. The industry’s wheels turn slowly. I didn’t expect to hear back for months, but after only a week—the equivalent of a publishing nano-second—I thought maybe I had emailed the wrong person, so I sent another email to a different contact at the agency. (Don’t do this.) Despite that lapse in judgment, the following email popped up on my phone only days later:

I had to read the message several times, because I couldn’t believe it was real. ATWOOD WAS GIVING ME PERMISSION TO USE HER GORGEOUS LINES IN MY NOVEL. I started crying, of course, because I was—am still—overwhelmed. Atwood required no payment, only attribution.

I don’t deserve this honor—have done nothing to warrant Atwood’s generosity—but I am moved beyond expression by her kindness. How grateful I am to Atwood. How grateful to be part of a literary community where a writer like Atwood allows a person like me to use her words. Her words remind me to be brave and hungry for this life, and also to be giving. I will remember to be generous, especially to those, like me, who are still finding their way.

This is also why I keep searching for the perfect card for Margaret Atwood, even though I’m certain I won’t find it. There are so many things I wish I could say to her. I want to thank her for shaking me and waking me up and keeping me company in the lonely darkness of creating. I want to share the vastness she helped me traverse and my fears overcome and the feeling of words—her words—giving me the courage to own my body and my voice. These things occupy the limitless expanse of my heart and could never fit inside a card.

hbandeen-

How freaking exciting is this!?!?! So…amazing. yay.

meagan macveeeeee-

It really is. I kinda can’t believe it.

Small Acts of Civility | Hot Pink Underwear-

[…] in the week, I wrote about choosing a thank you card for my literary idol, Margaret Atwood. In the essay, I gushed about Atwood and the impact her work has had on me. After posting the […]